When the Equity Risk Premium Turns Negative: What It Means for Stocks, Bonds, and the Dollar

When the Equity Risk Premium Turns Negative: What It Means for Stocks, Bonds, and the Dollar

With the equity risk premium below zero, bonds currently offer a better cash deal than the S&P’s earnings yield. That does not mean stocks have zero expected return, but it raises the bar particularly if interest rates drop as expected. If this regime persists, expect ongoing competition for capital, tougher multiple expansion, and a market that increasingly rewards real earnings growth over story and multiple.

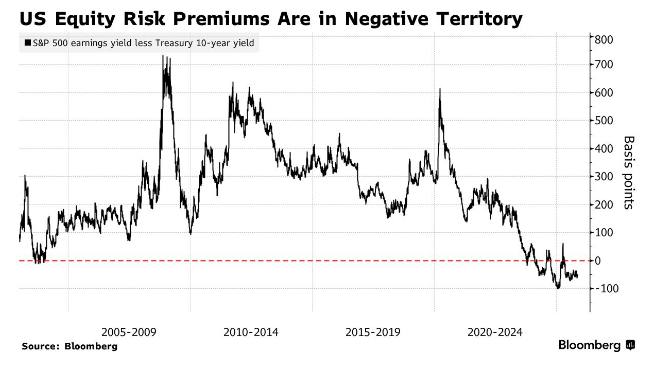

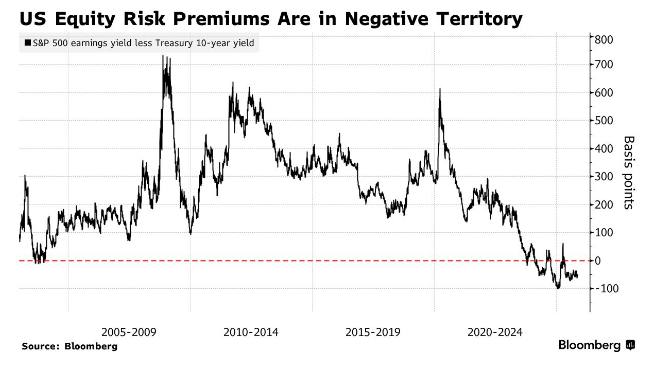

TL;DR: The U.S. equity risk premium (S&P 500 earnings yield minus the 10-year Treasury yield) is below zero. Bonds now pay more than the S&P’s earnings yield. That raises the hurdle for equities, makes multiple expansion harder, and can pull money out of stocks if this persists. If bonds remain attractive and gold stabilizes, the U.S. dollar likely strengthens as well.

What the negative equity risk premium means

The equity risk premium using the simple “Fed model” is the S&P 500 earnings yield minus the 10-year Treasury yield. When this spread is negative, investors are paid more to hold Treasuries than the index’s earnings yield. In plain English, bonds offer better cash-on-cash today than stocks “earn” on price, which tightens financial conditions for equities.

Why bonds look attractive now

• Higher yields: By recent standards, yields are elevated, so investors can lock in meaningful income.

• Carry today vs. growth tomorrow: Treasuries provide certain income. Stocks must deliver earnings growth and buybacks to compete.

Rates and flows: how money moves

• If investors expect rates to fall: Bonds are especially attractive because prices usually rise when yields drop. Flows often reach bonds before or during the decline in yields.

• If investors expect rates to rise: Long-duration bonds face price risk. Investors may rotate to cash, T-bills, or short-duration bonds instead.

Price–yield rule of thumb for a 10-year Treasury (duration about 8–9):

• Yields down 0.50% ⇒ price up roughly 4% plus coupon.

• Yields up 0.50% ⇒ price down roughly 4% but coupon still pays.

Longer duration means larger swings.

What this setup does to equities

1. Relative rotation: Some capital leaves equities and moves to Treasuries or money-market funds.

2. Valuation pressure: Higher bond yields lift discount rates, which compresses P/E multiples unless earnings accelerate.

3. Flow sensitivity in leaders: If large allocators rebalance toward bonds, selling pressure often shows up first in higher-valuation growth names, including the MAG7.

A simple playbook depending on your rate view

1. You think yields fall: Favor intermediate or long Treasuries for carry plus potential price upside.

2. You think yields stay range-bound: Ladder short-to-intermediate maturities to lock income and reinvest as bonds roll down the curve.

3. You think yields rise: Keep duration short with T-bills or floating-rate notes, or accept equity risk if you prefer growth exposure.

Credit vs. Treasuries

Corporate bonds add a credit spread that boosts yield in stable growth environments. They are more vulnerable if growth weakens or defaults rise. Treasuries remain the clean rate exposure.

Dollar and gold context

If bonds remain attractive and gold stabilizes, global demand for U.S. income assets can support the dollar. A stronger dollar typically tightens financial conditions for risk assets and can further challenge multiple expansion in equities.

Bottom line

With the equity risk premium below zero, bonds currently offer a better cash deal than the S&P’s earnings yield. That does not mean stocks have zero expected return, but it raises the bar particularly if interest rates drop as expected. If this regime persists, expect ongoing competition for capital, tougher multiple expansion, and a market that increasingly rewards real earnings growth over story and multiple.